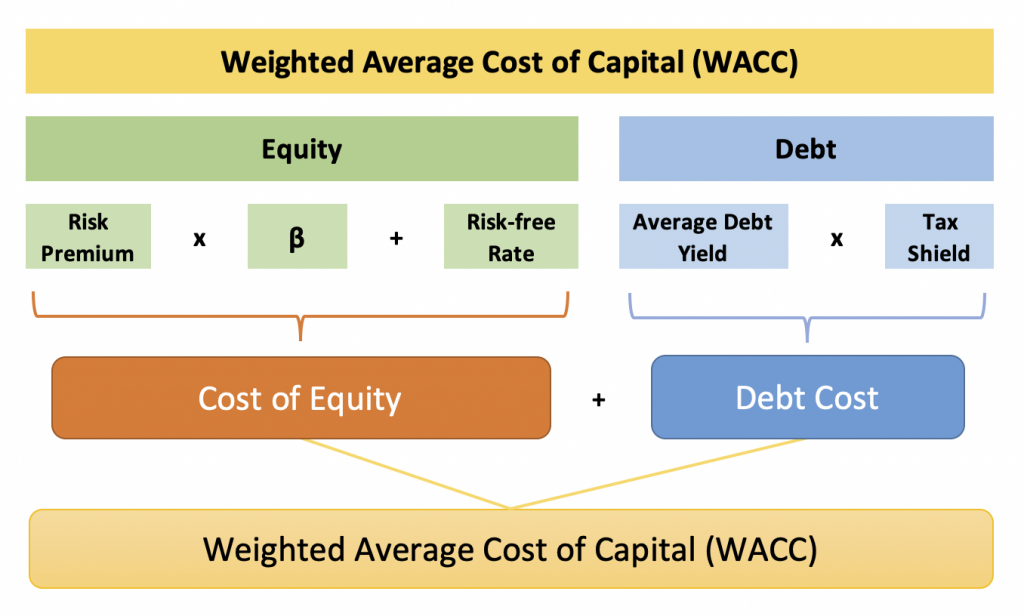

WACC, which stands for Weighted Average Cost of Capital, is something taught in finance or business schools pretty ubiquitously these days. It is essentially meant to reflect the rate which is paid by a business to finance its assets.

Having recently passed the CFA level 1 exam, I can testify that the sacred text (curriculum) contains the WACC gospel in all its glory. Judging by a recent experience, it appears as though devotion to, and faith in WACC is quite strong. Blasphemous as it may be, I’m about to make the case that WACC is the work of the devil, and will lead you astray.

When evaluating an investment opportunity, one typically looks out into the future and estimates a few things:

- What cash will this investment generate?

- How sure am I about this?

- What rate must I discount this cash at to arrive at its present value today?

That last one is the sticking point. Curiously, while explaining the time value of money, the clergy at the CFA institute will refer to such a discount rate as relating to forgone interest. Essentially they’d say that 100bucks today would grow to 100x(1+r) in a year where ‘r’ is the rate of return you can get on the 100 bucks. And by the same logic, if offered 100 bucks one year from now, one would calculate the amount needed today, which you can grow at ‘r’ to arrive at 100 bucks one year from now, and call that number the present value of the 100 bucks coming to you in a year.

Later in the texts however, cash flows generated by a business must be discounted at the WACC of the business. This is puzzling.

Let’s assume we’re looking at a strong business which generates enormous cash flows, and will never again need to issue shares to raise capital. Does this business have a “cost of equity”? One might argue that if shareholders don’t get a reasonable return on their investment they would either sell their shares, or vote for change in the board/management of the business to better reflect their wishes for returns. Both these outcomes seem like self-correcting events to me.

So how exactly does the WACC relate to, interact with, or impact upon the cash that a business can generate and pay out? I really don’t know. This heretical question seems to not cross the minds of those applying WACC in their investment decisions.

This is not to suggest that capital is free, just that WACC isn’t the answer to the fundamental question. Not having a clear-cut answer is likely the reason for the popularity of WACC. It’s easier to live with an incorrect answer than to live with uncertainty.

Some might argue that the riskiness of an investment should be reflected in an increased discount rate. I’d argue that the time value of money is not impacted by whether or not you forecasted the cash flows correctly. The rate at which one discounts a cash flow has nothing to do with the certainty of the cash flow. Expected value measurement (using weighted probabilities) of an uncertain cash flow may be appropriate to measure that cash flow, but to imply that because you can’t see into the future of business x, the rate at which your money could grow elsewhere changes is to conflate two very different concepts.

Further, using as an input the expectations of other investors in your calculations of a rate at which to discount cash is similarly erroneous. The expectations embedded in the valuations made by other investors do not affect at what rate your cash could grow elsewhere.

Clearly what I’m describing is “opportunity cost” which in economics simply refers to your best alternative option. Thinking in terms of opportunity cost is what I deem appropriate. I’m ready to be burned at the stake.